Playing With Fire

Before my son was even a teenager, we used to play with fire. Whether it was starting the biggest bonfire in the shortest amount of time, or creating the biggest bang using an old aerosol in front of a candle, which we would shoot with an air rifle from a distance, we always found ways to push the limits.

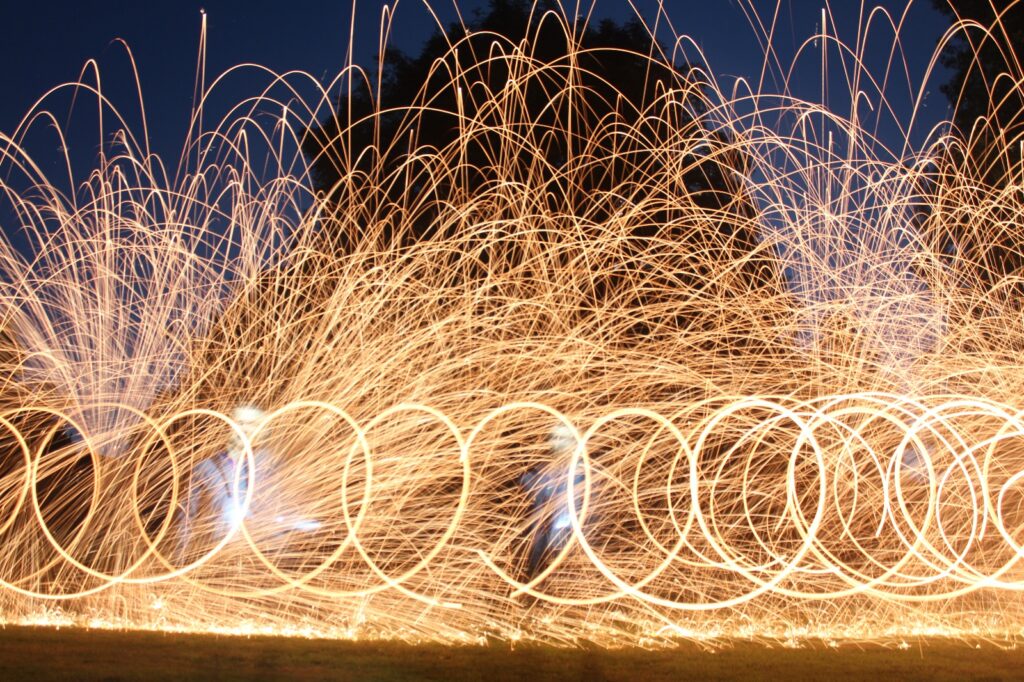

We would make rocket launchers using model rocket engines and create spectacular special effects by stuffing fine steel wool into a metal whisk, attaching it to a string, and then igniting it.

We would hold Roman candles while running up and down the garden, filming the display with long-exposure cameras just to see what it looked like.

We would also play with sharp penknives to make sticks, arrows, and spears. I was keen for him to grow up with all his fingers, so I taught him how to do it safely.

I can remember him sitting on my knee in my car when he was about eight, and I taught him how to drive. It might have been even earlier—perhaps six—since I remember he couldn’t reach the pedals, only the wheel. I could feel his excitement as he steered the car around the little plot of private land.

To many, this is a sign of a deeply irresponsible parent. How could I expose a young child to such risks? I completely understand that perspective, but it depends on whether you are teaching the child how to manage the risks, or just recklessly exposing them to danger.

At six weeks old, my son swam for the first time. It came quite naturally. Now, he has the confidence to swim, sail, dive, and drop into and around water in ways that even challenge me as his father. When we went scuba diving together for the first time in Egypt, when he was in his late teens, he took to it like a fish.

Around the same time, he jumped out of an airplane too. On that particular Saturday morning, he had no idea we were about to head out to Beccles in Norfolk for his first skydive. The way he dealt with his mum’s concerns was classic—it was far better than how I had dealt with it.

Just as the picture at the start of this looks dangerous,

considering my son is in the middle of it, I would like to state that I took

full responsibility for our safety. If anything had happened during that

skydive, I was acutely aware of how much trouble I would have been in.

I would prefer to say that teaching someone to deal with

risk is of far greater value than teaching them to avoid it.

In the UK, we live in a culture that wants to mitigate risk,

which is sad, because living and progressing inherently carry risk. In

business, there’s a culture of risk assessment associated with everything,

which makes progress, or the use of common sense, almost impossible.

The only way to remove risks is never to expose yourself to them, which, as far

as I can see, means not actually living. You couldn’t go out, cross a road, eat

a meal, form a new relationship, drive a car, take a bus, or go to a firework

display. Life carries risk, and the real question is: are we teaching young

people to deal with risk, or simply to avoid it?

Now, back to that dramatic photo. My son is in a piece of play equipment in Trowse, Norfolk, where I used to live. He is spinning a metal whisk containing smouldering steel wool. If you had been there when it happened, it would have looked really boring. But in the long-exposure photo, it looks spectacular. How often do we see images that look spectacular but, in reality, aren’t?

My son is thriving, and the play equipment is still there. Nobody was harmed,

but in that photo, two people were enjoying themselves, and both father and son

were being responsible. Both took responsibility seriously and dealt with risk.

Both created wonderful memories for each other.

Sadly, within the current culture in the UK, there seems to be a reluctance to take risks, out of fear of what might happen. Faith and trust have been replaced with fear and compliance. I’m not sure how many people stop to consider if this approach works. I don’t think it does. This mindset has a tremendously dehumanising effect on people and creates environments that look more like zoos, with all their cages and barriers, than places where people want to live and thrive. It also makes innovation and progress difficult, because both of those things introduce risk, which the prevailing culture wants to mitigate against.